September 19, 2011. Netflix's Reed Hastings: "I messed up" in communicating price increases

October 10. Netflix backs off - a little - from their radical restructuring

October 20. Opposing Views: Netflix restructure - bold embrace of the future or customer debacle?

October 23. Reed Hastings reflects on Qwikster & pricing controversies

April 10, 2012. "Strategy + Business" magazine says "Netflix wasn't all wrong" in its strategic changes (See the tide of opinion beginning to turn?)

If you need a quick recap, here goes. That summer, to capitalize on the growth of streaming media (and, possibly, to hasten the customer transition from the legacy DVD-by-mail business to streaming), the company announced separate pricing for DVD rental and streaming. The total price for customers signed up for one DVD & streaming would rise to $16 per month a 60% increase. Then, in October, Netflix announced that it was splitting its business into two parts - DVD-by-mail (to be renamed Qwikster) and streaming (keeping the Netflix name). Customers would soon have two separate accounts to manage, in addition to paying more.

Fallout was widespread and intense.

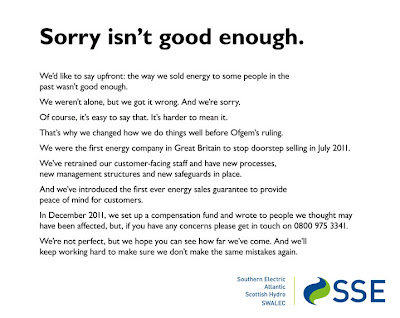

Within a week, CEO Reed Hastings said he "messed up" and apologized to customers. Two weeks later, Hastings pulled back on separating out the DVD-by-mail service and ditched the Qwikster name. The price increase, however, stayed.

Last week, eighteen months after Qwikstergate, Netflix announced stellar quarterly growth numbers, basked in rave reviews of its original series "House of Cards" and enjoyed a stock price that was the largest riser among the S&P 500 this year (of course, the stock is still below where it was before Qwikstergate broke).

So, while the crisis did not end up being what the New York Times' James Stewart called a "near death spiral," there is plenty to look back on now. What did Hastings learn from the experience? Here's what he told Stewart:

Mr. Hastings said he realized that the company’s attempt to both raise prices and separate into two companies, one the legacy DVD-by-mail business and the other the up-and-coming broadband streaming business, was trying to do too much too fast....

“[To bounce back from the crisis,] there was amazing pressure to come up with the shiny object that would make everything better,” he said. “But the phrase I used was, ‘There are no shortcuts.’ We weren’t going to find an idea or gesture that would make people love us again overnight. We had to earn their trust by being very steady and disciplined. And we had to be careful because we were on probation. We had to stick to what we do well and not lose confidence. I couldn’t say for sure we’d recover. But I was confident that our best odds were to be very steady and focus on improving the service.”...

With this week’s developments and the stock over $200, “in one sense I can say this is behind us,” Mr. Hastings said. “But it’s like a partially healed bone. It’s still quite fragile. Were we to make a similar mistake, we’d be right back in the penalty box. So we’re not really out of the woods. We’re growing and we’re making good progress, but we’re still not fully back to where we were.”

I am struck by Hastings' combination of humility and confidence. When things were difficult, and people urged him to find a "shiny object" to make everything better, he had confidence that his general strategic direction was correct and kept his patience. Now that growth is returning, he is not bragging - instead, he realizes that "it's still quite fragile."